I was born in Haiti, in Port-au-Prince. But I came to Miami when I was about six years old. I remember kissing my mom goodbye at the airport. She had this bright, plastic-red lipstick. I remember her giving me a kiss, and I remember feeling that kiss years later. It was the last time I saw her for a long time.

When we came here, it was just me, my two siblings—my older brother and my sister—and my father. Our father worked in import/export—buying merchandise here and then going back to Haiti—so we never really saw him. He was kind of dipping. At a certain point, we started to raise ourselves. But I learned how to cook from my father. My mom just came here two years ago, so this is her second summer in New York. It’s my first time living with her since I was six. Now I come home to the shit that you were supposed to get as a child. I’m getting it in my twenties, which I think is when you actually need it the most.

My mom likes New York because you can work here. You can use your hands, and that’s the Haitian way. That’s our culture. We’re people who, like most humans, do labor. But unfortunately in Haiti, your labor doesn’t always get you what you need to support yourself. So the fact that she can do that here and be part of my life again after a couple decades—I think she likes that about America.

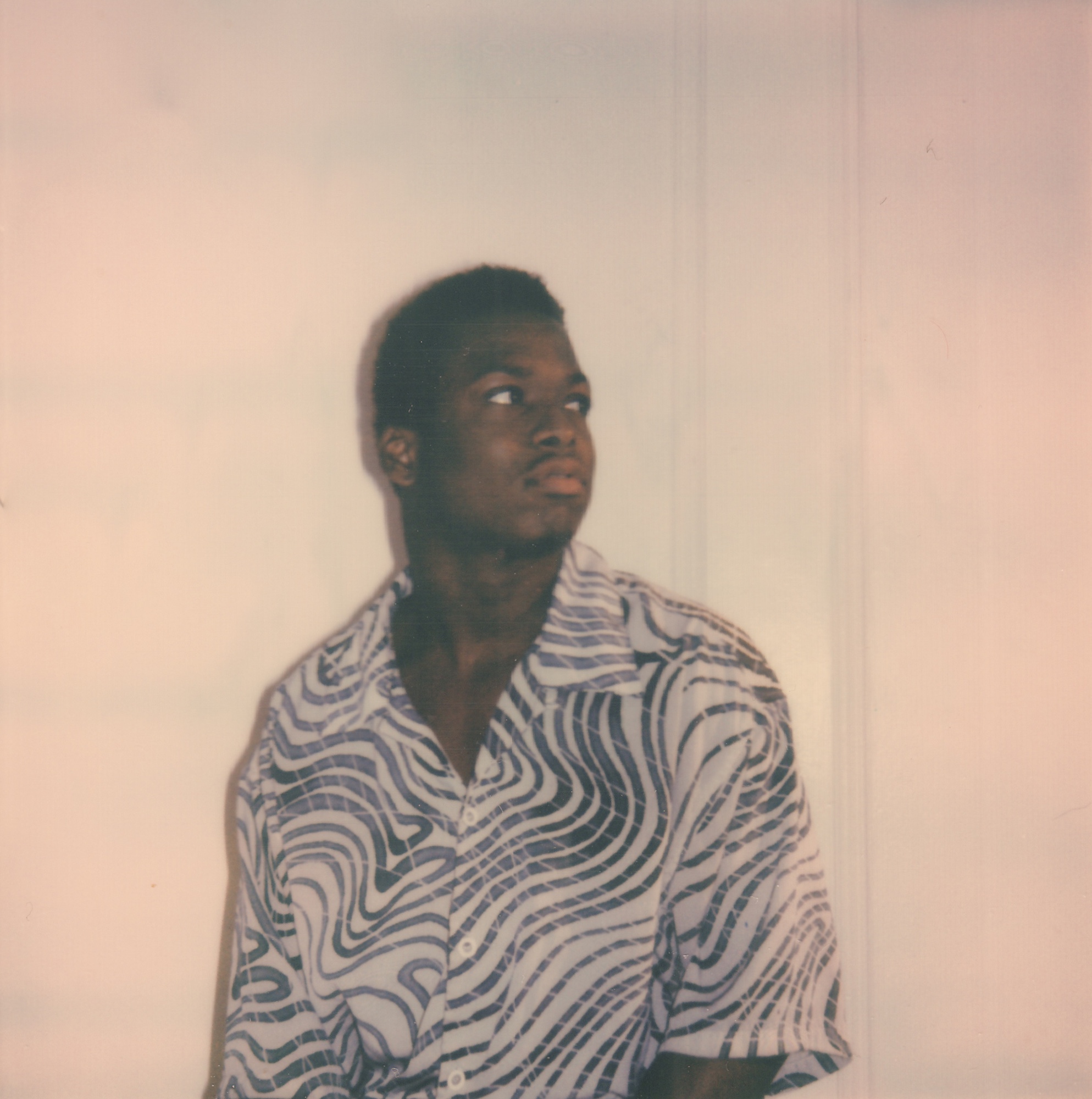

Youth programs built me. I didn’t think much about it back then. But we grew up in the hood, so having these free programs after school gave me a place to go and do me. My first exposure to photography was through youth programs, specifically not-for-profit arts programs. I had a professor named Noelle who was the first person to introduce me to photos. I’ll never forget the power and magic of her just showing me these images—seeing pictures and feeling like you’re on another planet. I loved portraits of people, how you could see the human in them. You could see their struggle, their happiness, their everything. Those pictures changed my life, in a way that music or film couldn’t. Just the weight of a picture.

I started shooting in eighth grade, and I never really stopped. It’s something that I knew I was good at, but I don’t want people to ever think it was easy or that other people always loved them. I took the classes. I’ve had my work shit on. I’ve left the studio with a little bit of a tear in my eye—I had all those moments. I went through all the feelings that I think anyone in their field feels when you’re just trying to achieve what you’re taught is greatness.

Every photographer will talk about the “special light” they have wherever they’re from, but I think Miami has a really special sun. I knew everything about the sun in Miami. I knew when to shoot, I knew the positions of the clouds, I knew how long it took the clouds to go from here to there. I was really focused on it. It was like my studio.

When I moved to New York—god, I was homesick. I never thought I could get homesick. But Miami has all of these little crevices and sets and things to just play with. Someone’s front porch would look amazing. Just the warmth and the cool—it’s a certain light. But all of Brooklyn looks alike to me, so building my own sets for shoots came from me being away from Miami, from that resource, from the light and the people and the natural scenery there. I’m also a designer, so making a set just felt really right.

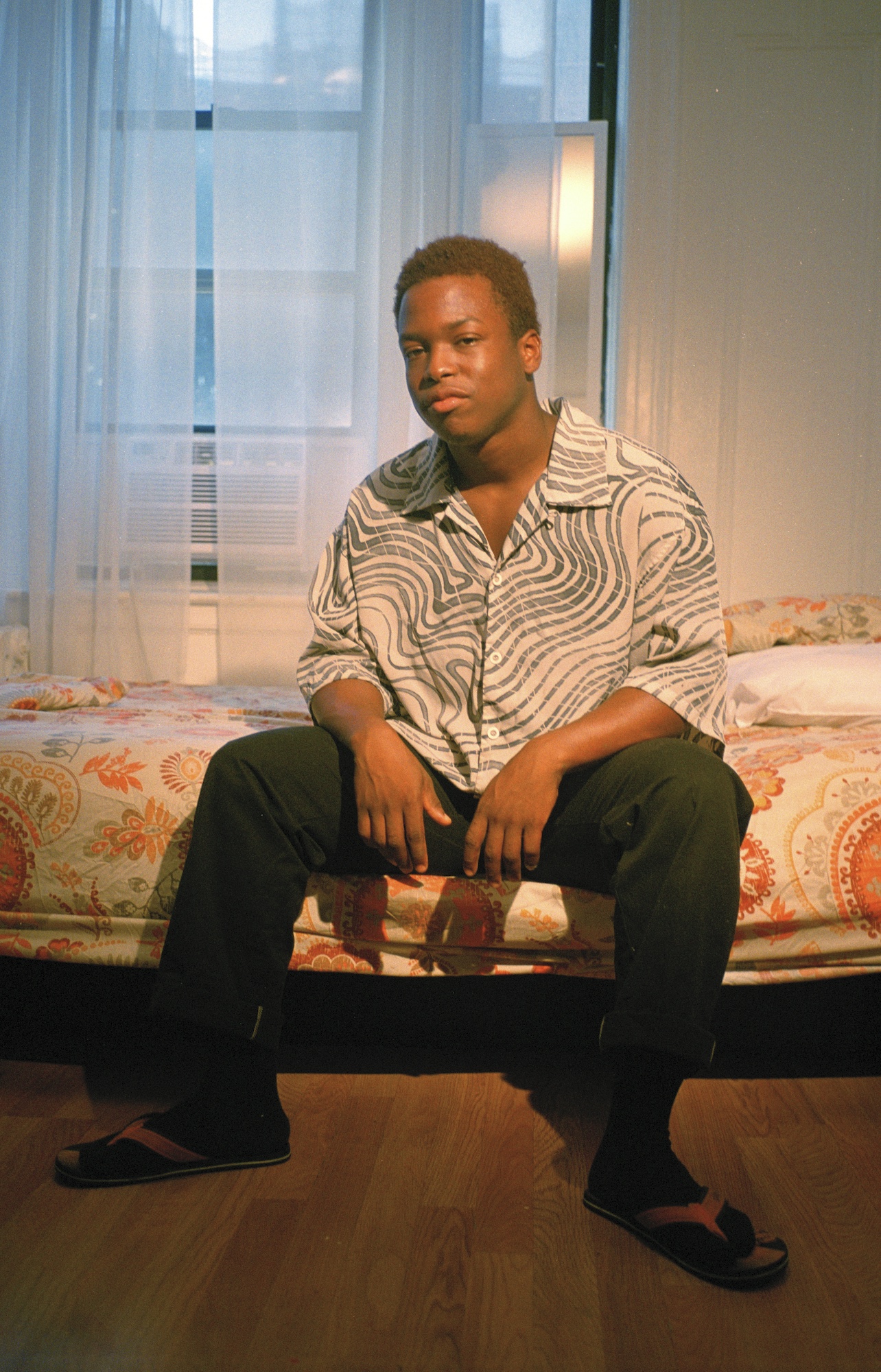

At school, we had these long 40-inch color printers and it would only cost me a few bucks a print. So I would print these bougie 17th-century French wallpapers and put them all over my dorm. For my first shoot, I invited all my friends over to do a little shoot about hair. The sets just got more sophisticated from there. I just started building what I wanted, building things I didn’t have access to, and building from memory.

Growing up in a Haitian household defined a lot of my notions about life. Our home never felt like the homes of “normal people.” Now, when I say normal people, I grew up watching Malcolm in the Middle and shows you’d consider “white television.” That was the standard of what a home should look like. The idea that things are always well-placed, or always clean. Or minimal. Or Western.

Since our father did import/export, our crib never looked like that. Our home became like a storage unit. We always had, like, five extra chairs and a fridge in the living room, and in the kitchen, an AC that was going to be sold for double the price. I would come home to a toilet in the bedroom. Items were always misplaced. But there’s also a creativity to being broke as fuck. So many things play into shaping the way your home looks, from your culture to your class. Just like you as a person.

So my sets were interpretations of what I had grown up with as a child and as a teenager, trying to recreate those moments. I had all those journeys, and it’s what I’m presenting to the world now.

I just want to say, if any young person is reading this, there’s an illusion to “making it.” You know, my homies will hit me up on Instagram like, “Oh baby, you’ve made it!” But I’m like, “Nah, boy, my rent’s still three weeks late.” There’s a competitiveness in the art and design fields that people don’t really acknowledge. I get it in fashion, but in photography and art, there’s a silent competition for these grants and these opportunities. Everyone deserves a goddamn review. Really, it doesn’t matter who it’s from.

I was given the opportunity to meet all these really awesome editors, which is a step away from getting whatever story you’re trying to do recognized and noticed. I’ve learned everyone’s connected. That’s another magic in New York: invisible things happen behind your back because you were just in the right place at the right time. Shit like that don’t happen in Miami.

I think as I get older, I’m looking for a different kind of validation. In the beginning, it was getting into college. Actually, it was about getting a goddamn scholarship. That was important: I needed the money. People always say, “You don't need any validation”—that’s bullshit. You need that shit for your spirit, and just for the work that you’re doing. For example, it’s dope that The New Yorker did a story about my show. But Haitian people weren’t at the show. Only the ones I invited. I want validation from my community, the community that’s given me so much culture and language and spirit. I’m separated from the Haitian community right now. Look where I live: Bushwick. If you know anything about Bushwick, it’s that it’s all young, mostly white creatives and the New York natives. I get along with everyone, but those are not the people that I grew up with. So, I’m always looking for validation from the Haitian community. The Haitian community has never given me props.

I love the part of being creative where you just straight-up want someone to be like, “This is visual ecstasy. This work is sexy. This work’s delicious.” I love that, too. Forget about culture, forget about class, forget about all that, just think about good work, you know? That will always be something I chase. But I want that same response from people in my community. From Black folks, from Black publications, from Haitian publications. The people who grew up in the Caribbean . . . what do they see?

I grew up in the hood, but I was friends with all the rich kids, so I would go over to the other side, the nicer side of Miami. They would just have so much fucking weed. Those were the days when it was fun, because we were young and we were just trying to see how high we could get. Everyone loves that point. It’s an adventure, it’s like, “Let’s see if we can take another bong hit.” It was fun, you know?

But I was someone who could never function high. I couldn’t be creative high. Everyone talks about all the amazing things they could do stoned, and I’m like, “Why can’t I do it?” The only thing I could do high was have great sex, nothing else. But somehow I always got in trouble for weed.

One of my most vivid weed memories was in eighth grade, which was when everyone started smoking. A kid told me he wanted some weed, and at the time I knew people who were selling. So this much older kid gives me the weed to sell to him, and I’m only in eighth grade so I’m really dumb. I don’t know anything about the smell of weed.

I brought it to school in a little medicine bottle. I’m in history class and the whole classroom smelled like weed. This one girl literally pretended to have a panic attack in class—“I can’t breathe!” So the teacher called security and my heart’s pounding. All the clever street shit that I had learned disappeared because I’m just in panic mode. I’m thinking, They’re going to find my weed and I’m going to go to prison forever.

Security comes to the class and they’re calling row by row to check bags. The intensity is building up because he’s about to get to my row and I go, “Okay, okay, it’s me!” and everyone turns around. We walked over to his office and he’s like, “Really? I thought you were joking. It’s you?”

The principal got there, and this man was an asshole. I remember hearing the sound of the walkie-talkies of the police coming into school and thinking, Wow, I really fucked up. Because my parents weren’t there and I had one job, and that was to stay out of trouble so that the government wouldn’t start looking into our family situation.

They took the weed and put it in a little evidence bag, but they didn’t put me in handcuffs. They took me to a police car and everyone’s staring at me, and I’m just like, “Fuck, my life’s over.”

My sister lived down the block at the time and the cop did something I will never, ever forget. She told me, “I could get fired for this, but this is the one chance you’re going to get in life.” And then she drove me up to my sister’s house. Dropped me off at home. She was supposed to take me to the police station.

Now that I’m older, and I’m watching all these documentaries about marijuana and the history of it, I think a lot about laws. I don’t like to think about my Blackness. I say that not in a fake way, but I mean I don’t want to go through the world thinking about my race. But in that moment, there I am, a Black kid in this bougie art school caught with weed—I fit into this box. There’s this system of weed laws that will fuck up your life.

Back then, I wasn’t thinking about it. But now I realize, if not for that cop, I don’t think I would have gotten here. You can’t get scholarship money from the government if you have a record. So, I would love to give you great, light stories, the same weed stories we all have. But that’s not this one.