My parents are classic Boomers. My mom was a hippie, and though my dad wasn’t really, they were definitely leftists in their day. But when I was I growing up, they were going through a born-again Christian phase. I was raised in a town called Wheaton, Illinois that is a fundamentalist Christian haven. Wheaton College is there, which they like to call the “Harvard of Christian colleges.” That’s a name they self-apply.

I grew up around an interesting strain of fundamentalist Christianity that has this sort of pseudo-intellectual thing going on, in which they love to debate readings of the Bible and the various ways that it’s all true. It’s almost a sport. It’s amazing what contortions people go through to say that the Bible is all real. But these people were also my teammates on cross-country, they were in my classes—I grew up with them. So it was impossible for me to be totally disdainful of them, but it was also impossible for me to agree. I had friends tell me that they were worried I was going to hell. They would come to me out of concern, of course, but I found it very condescending.

So I formed a very strong opinion against that sort of Midwestern upper-middle class politics—which tend to be conservative—and megachurch culture. But I also learned how to talk to those people and have a real debate. I think if I had grown up on one of the coasts, I probably wouldn’t have been forced to consider those points of view. Maybe I would have a harder time with where that mentality is coming from, even though I've never really related to it. But I also just wanted to get out, so all of this helped drive me to escape.

My ticket out of the Midwest was NYU, and I've been here ever since. My best friend from high school lives here and other friends got out, so there are a few of us. I mean, look, Wheaton's 25 miles from Chicago; it's not completely cut off from reality. And yet it is, it really is.

I'm still interested in religion and spirituality—I studied that in school. And I'm still a fan of Jesus. I’m interested in Buddhism. I meditate. I think there is a spiritual dimension to the universe. I feel like there has to be, because our perceptions are so limited. I’ve read a lot of Carl Jung, and things like synchronicity seem metaphysical. Maybe it can be explained with science. I think spirituality and science are on a collision course. I also think the passion of religious people is inspiring. There's a discussion about what life is about that you don't necessarily get in a secular community.

The other thing that I extract from Christianity is this idea of loving your neighbor and proceeding from a place of a loving heart. I think it is immensely beautiful and kind of the only way forward for humans. I just wouldn't ever practice it as a Christian, because I think that creates division. I hope someday I can find a way to talk about it in my work that’s not cliché, because I feel like you hear that and you're like, "Okay, this is a bunch of bullshit."

What does it mean to actually proceed from a deep belief in love for other people? To actually walk through your life that way, with every decision that you make and every interaction that you have proceeding from that? As opposed to, “What can I get from this person?” or “How is this person in my way?” or “How can I get more for myself?” Not because I think there's a god judging us when we do that, but I think it just doesn't make us happy. This is the oldest message and we still haven't learned it. I think all of us are like, "I'm gonna be the one that finally figures out how to just be selfish and be happy." But it never works.

After school, I PA’d on commercial shoots. I was living in Bushwick. There really wasn’t a lot of work in 2004, but I just remember driving a lot of cube trucks. Some friends from school—one of whom is Jon Watts who now directs Spiderman movies—and I started our company called Waverly Films. It doesn’t exist anymore. We just went down to some place in Greenpoint, a notary public, and started a business for, like, $700. We started producing music videos.

We did anything we could. We would literally do everything. Any song that was sent to us, we would make a music video for. We did a bunch for sort-of-bad UK house music. But we did Fatboy Slim. I directed videos for DFA Records. A small video I made for Juan MacLean got seen by The Rapture, so I made three videos for them, and then James Murphy saw those, so I did a video for him. The DFA thing kind of got me going.

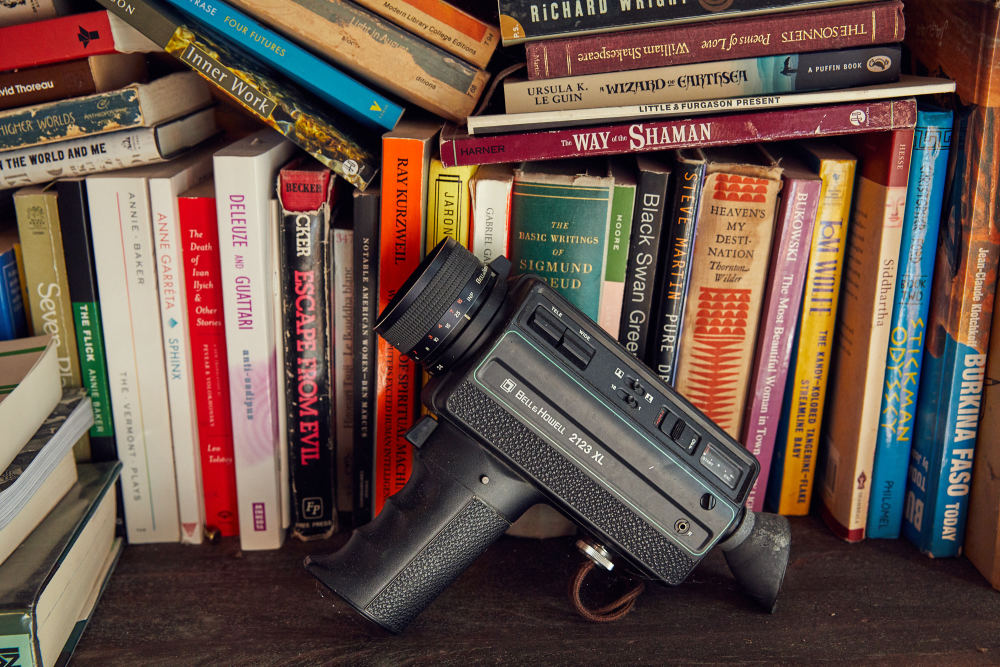

The Dispossessed, if you haven't read it, is one of my favorite books of all time. It's sort of a treatise on anarchism, but in a sci-fi story. Ursula K. Le Guin’s approach to sci-fi is also my approach, in that she uses the sci-fi premise as a way to explore human dynamics. I guess that's what sci-fi is supposed to be, though that’s not often the case. Le Guin uses it to explore relationships and political systems.

I've only made one sci-fi movie, Creative Control, but the next couple are also sci-fi, so I guess I make sci-fi movies. I think we're living in science fiction times. With smartphones and things like that, we're already there. It's almost impossible to talk about any issue without also talking about technology. It's a very important time for the genre.

I was living in New York when September 11th happened, and after that, there was a scene change—for everybody, but especially those of us here. We were living in a police state for a few weeks. It was very strange to suddenly have guys with fucking military grade rifles patrolling the streets and going through checkpoints. And that’s when I started formulating the idea for the two movies that I'm getting ready to make. Way back then.

It’s a slow process. I’m a little bit removed, as the producers are mostly handling getting the money together for the film, but basically we need a star. The movie has a lot ideas about class and race that are definitely not mainstream. Or they’re becoming mainstream, but that’s the weird thing: sometimes you think culture is ahead of where it is because of what makes headlines. But when you actually go into the corporate world where lots of money is being spent, it’s extremely conservative.

I mean, it's insane. You have Nike using Colin Kaepernick as their campaign star, and you're like, "Okay! We've really made a huge leap forward." But when you actually go into these conference rooms and you try to make a movie that even just has a Black lead in this day and age … it's just amazing how conservative it still is.

The thing about commercials–and companies in general—is that they don't make culture, they follow culture. If they think having an interracial couple in a commercial is going to make them more money, they'll do it. It just takes a long time for suits to accept that that may be true, even though you could have told them that 5 or 10 years ago. There's no integrity or morality in corporate culture. It's only about money. They'll follow progressive politics if they smell money.

I always thought if I got arrested, it would be for protesting. So when I got arrested for smoking weed, I felt stupid.

Not long after September 11th, my buddy and I were walking down the street smoking a spliff—as we did all the time in the East Village—and I noticed a homeless guy in a stained trench coat with a 40 bottle sitting against the wall. As we walked past him, he jumped up and started following us. I was like, "Oh, no, what does this guy want?" He reached up and grabbed my arm that was holding the joint and said, "What do you got there?" and I spin around to see that he has a chain around his neck, and on that chain is a badge. Everything goes into slow motion and I think, "Oh no."

Two other cops come huffing and puffing across First Avenue and the three undercover cops push us up against the window of a Japanese restaurant, our faces smashed against the glass. As they were handcuffing us, all I could manage to say was, "What's happening?" And one of the cops says, "You're getting arrested, dumb fuck!" They took so much pleasure in this.

They threw us in the paddy wagon and we spent the night in jail, in central booking off Canal Street. But the thing about that experience is that there must be 20 cells in the catacombs down there and my buddy and I were the only two white dudes in all of them. It was shocking. We hear the statistics, but to actually see it is pretty upsetting. It was like, "Well, this is obviously not right." The other thing was that you're sitting in the cell with 15 other dudes, and everyone talks about why they're in jail. Everyone was like, "Weed. Smoking weed. Smoking weed. Selling weed. Smoking weed." Everyone was in jail for weed. There were a couple of dudes in there for soliciting prostitutes, but everyone else was in jail for weed.

Being in jail is horrible. It's a horrible experience, I never want to do it again. The way that you're treated is just awful. Like you're not a human being. And it was clear that they were just going out and looking for people to arrest. This was Giuliani time. There were quotas, and they were actually going out and arresting people like it's a game. And then seeing the people who are suffering because of that game—it was eye-opening. I think once you open your mind to that kind of stuff, you see it more, and you can’t unsee it.

Now I don't really use cannabis recreationally anymore. I see it as medicine. I use it for anxiety, I use it as a painkiller. I like a beer's worth of weed: you're not stoned, you're just sort of buzzed. And it’s cool that now I can actually get what I need. The specific dosage and the right strain and all that. There are a lot of cool things about the wave of legalization, and one is that people can really use it as medicine more. But they can't legalize it without addressing all the people in jail.